Journal of Social Philosophy 27 (2): 176-186. 1996.

Abstract

The political distinction between left and right remains ideologically muddled. This was not always so, but an immediate return to the pristine usage is impractical. Putting a theory of social liberty to one side, this essay defends the interpretation of left-wing as personal-choice and right-wing as property-choice. This allows an axis that is north/choice (or state-free) and south/control (or state-ruled). This Political Compass clarifies matters without being tendentious or too complicated. It shows that what is called ‘libertarianism’ is north-wing. A quiz gives the reader’s Political Compass reading.

Pristine clarity and modern confusion

The modern political left/right division is too crude to accommodate many important political positions in a way that makes any sense. Libertarianism (or extreme classical liberalism) is sometimes placed, often implicitly or vaguely, somewhere on the extreme right. But can we say whether it ought to be to the right or left of other ‘right-wing’ ideologies? How are we to indicate the extreme tolerance of personal choice (as regards drug use and consenting sexual practices, for instance) that libertarianism entails but which is not normally thought of as being right-wing?

Samuel Brittan sees clearly the confusion in the modern left and right (though assuming a libertarian view of liberty):

The dilemma of the [classical] liberal is that while Conservatives now use the language of individual freedom, they apply this only—if at all—to domestic economic questions. They are the less libertarian of the two parties—despite individual exceptions—on all matters of personal and social conduct, and are much the more hawk-like in their attitude to ‘foreign affairs’. Labour, on the other hand, has liberal instincts on foreign affairs and personal conduct, but is perversely blind to the claims of economic liberty, which is distrusted as a capitalist rationalisation. (Brittan 1968, p. 131)

The original political meanings of ‘left’ and ‘right’ have changed since their origin in the French estates general in 1789. There the people sitting on the left could be viewed as more or less anti-statists with those on the right being state-interventionists of one kind or another. In this interpretation of the pristine sense, libertarianism was clearly at the extreme left-wing.[1] This sense lasted up to as late as 1848, with Frédéric Bastiat sitting on the left in the National Assembly. In Britain, it was the Fabians in particular who adopted old Tory ideas, asserted that they were more to the left than free trade, and labelled them as ‘socialism’ (Rothbard 1979). In the wake of the Fabians the old left and right has been muddled. It might be thought that there is now a swing back to the old labels. For instance, the Russians now call the Communists ‘right-wing’. But it seems that they are mainly following the West in using ‘right-wing’ as a pejorative.

A return to this original meaning would fail to make important distinctions that currently dominate political thought. One problem would be that any existing left and right groups with mirrored policies of state intervention in personal and property matters (say, 40/60 and 60/40) would, confusingly, find themselves at the same point on the right-wing of the political line. The modern left-right view is also extremely popular: virtually everyone has some conception of what it means. People have often tried and failed to show what is wrong with it and how it can be replaced (some examples follow). That they have failed is a sign of its stability. These two facts make it impractical to convince people of the virtue of an immediate return to the old distinction.

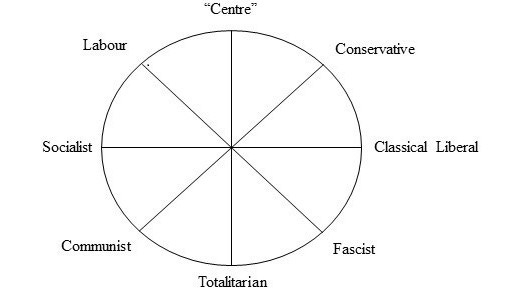

So a single political line provides no solutions to these problems. As a result, it is sometimes suggested that the political array is better viewed as a circle in which the extremes meet: the extreme left and the extreme right differing more in rhetoric than in reality.[2] There is undoubtedly some truth in the idea about differing more in rhetoric than reality. Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union have often been taken as extremes of right and left. But behind the political labels they look practically identical rather than opposite. People often admit the Hitler-Stalin similarity, yet that does not stop them thinking that Stalin is left and Hitler is right and that the market must somehow be on the right (being the opposite of communism).[3] Hence, in their confusion, they can only come up with a circle (figure 1).

Figure 1

It is hard to see how the political circle has better real explanatory value than the political line. The circle fails to distinguish the distinctively left and right elements both from each other and from other political elements. Perhaps this is because the idea of a political circle is not inspired by a desire to clarify matters but by a dogmatic delight in a paradox that seems to make all extreme political views inherently absurd. But the circle may be a useful first stage for illustrating the confusion in the left/right view, for the paradox does not withstand serious investigation.

Having an axis to grind

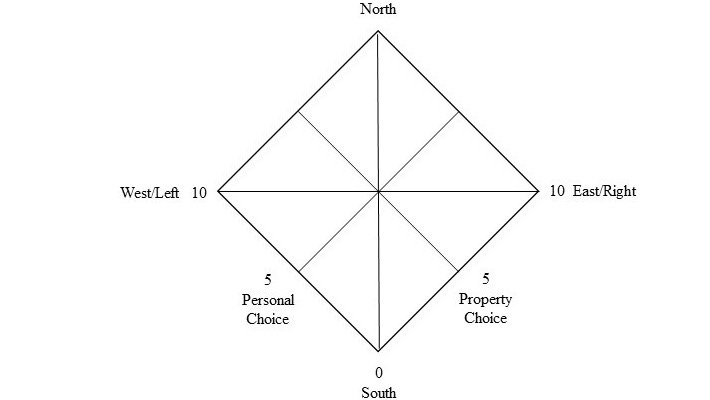

One idea that makes some sense of this confusion, or conflation, is David Nolan’s diagrammatical distinction between economic and personal liberty based on the empirical work of professors William Maddox and Stuart Lilie (1984). Nolan puts both types of liberty in the same diagram along two axes. But in my version I use the more neutral term ‘choice’, to be contrasted with (state) ‘control’. I also prefer ‘property’ as being slightly clearer than ‘economic’ (figure 2).

Figure 2

In figure 2, libertarians and classical liberals then find themselves in the top right-hand corner. Authoritarians, including paternalists, are in the bottom left-hand square. Fascism[4] is in the extreme bottom left-hand corner, being the very opposite of libertarianism. ‘Left-wingers’ are somewhere in the top-left square, with left-wing (anti-money and anti-private property) ‘anarchists’ in the extreme top left-hand corner. ‘Right-wingers’, possibly with certain religious fanatics in the corner, are somewhere in the bottom right square.

So perhaps it is a clarificatory caricature to view modern right-wingers as personal state-controllers and left-wingers as property state-controllers. The contrasting distinction is between control and choice (no state-control) over both categories. The clarity of these distinctions enables us to avoid Kedourie’s risk of “guilt by association” (1985, pp. 143-147) whereby what is not left is automatically right.

This diagram makes things clearer, but it fails to incorporate the left/right view as simply left and right. It also fails to give us a felicitous analogous expression for the alternative choice/control distinction. But what if we follow Marshall Fritz (Bergland 1990, pp. 22-23) and rotate the diagram 45 degrees anti-clockwise? (Again, I use my preferred distinctions: figure 3.)

Figure 3

In figure 3, left-wing and right-wing are now to the left and right of the diagram. And we are able to describe the choice/control contrast as ‘north-wing’ and ‘south-wing’. With this distinction, libertarians can position themselves on a Political Compass.[5] The expression ‘Political Compass’ has long been used, but not much sense of it has been made before as far as I am aware.

In the UK, Jacobs and Worcester have produced a recent attempt to sophisticate the political spectrum that is less successful (1990). The questions they ask often presuppose state-intervention and so the categories arrived at do not allow for a choice/control distinction. Maddox and Lilie share one flaw in their approach. They are too focused on the centre of politics and so cannot make sense of the various extremes. It is misleading to categorise, as Maddox and Lilie do, 18% of Americans as ‘libertarians’ in any serious sense of the word. Also, their four boxes ignore other reasons for wingedness than being Liberal, Libertarian, Populist, or Conservative.[6] Unlike their boxes, the Compass allows for greater precision of direction and degree, and without specifying the particular ideology.

Brittan comes back to left and right in a later book (1973). He quotes the conclusion in Political Change in Britain[7] that most people “have wholly atomistic responses to the issues of politics” (p. 356). Though he notes that “statistical psychologists have found significant, although moderate, correlations between views on different issues which enable them to locate ‘opinion clusters’” (p. 358). So Brittan gives up the attempt to clarify left and right in the way he did in his earlier book. He sees the search for independent dimensions as mistaken, and concludes that “what different attitudes and individuals, who are characterised as left or right ... have in common are ... ‘family resemblances’” (p. 363).

He then gives a list of beliefs “a sufficient combination” of which “will justify the label ‘left-wing’ in a broader sense than mere proneness to vote Labour” (p. 363). He later gives a breakdown for Conservative political attitudes (p. 366). What he apparently fails to see, or fails to see the significance of, is that the left-wing views are overwhelmingly about state-control in property matters with choice in personal matters, and that the other list is the opposite. This is what sorts out the modern left and right; and this also suggests the single alternative choice/control scale. Having values that fit better on that scale enables us to avoid the crude view that “people are inconsistent”, as Maddox and Lilie observe (1984, p. 33), when they do not fit along left and right.

Instead, Brittan tries to make sense of these views by suggesting labels that qualify which kind of left or right is under discussion. But this discourages clear extremes at odds with the general left/right scale. In particular, it discourages something that Brittan says he would value: “a return to a party division in which one side puts together, in Cobdenite fashion, freedom in all its aspects and non-intervention overseas” (1973, p. 371). But he fears that “if the authoritarian party happened to be in power for the greater part of the time, the outlook for freedom would be dim...” (p. 372). It appears that his one-dimensional approach prevents him from seeing that the whole political consensus can simply move northwards so that both, or all, main parties would opt for less state control.

A simpler diagram

The previous diagram is more complicated than is necessary to convey the basic idea. A simpler diagram (figure 4) is possible, taking the clue from the earlier Samuel Brittan (1968, pp. 88-89)[8]: a single vertical choice/control axis can form a cross with the horizontal personal/property choice axis.

Figure 4

However, though this is an easier idea to grasp, it does not work for plotting political positions directly (it is not itself a Cartesian diagram—and nor are Brittan’s—it just looks like one). With the way I have set up the questions below, it will be necessary to work out one’s political position on the previous diagram first.

Tendentious axes?

It might be thought that this distinction between personal and property choice is tendentious. I shall consider four criticisms along these lines:

1) The Compass ignores the socio-economic, or class, bias of left and right.

2) The nature of liberty is too controversial to call one Compass point ‘libertarian’.

3) The personal/property choice distinction is not coherent.

4) Equally important dimensions could further be distinguished.

1) Is it misleading to ignore the socio-economic, or class, bias of left and right?

The west and east wings are partly stipulative and not intended to capture all that is in the notions of left and right wings. One thing that is ignored is the supposed socio-economic bias of the modern left and right: that there is some slight statistical tendency, in the UK for instance, for Labour to find more votes among the lower socio-economic groups and Tories among the higher.

For one thing, compared to the overall Compass such slight differences are trivial. For another, these differences can be seen as, in practice, reflecting vested interests that cause everyone else to suffer, including those of one’s own ‘class’. In any case, if the Compass questions produce a three-dimensional bell-shaped distribution curve then that indicates the capture of something socio-ideologically significant, rather than arbitrary groupings of ideas. A failure to be bell-shaped might indicate that the population can more clearly be interpreted along different ideological lines. But this does not in itself show that the Political Compass does not make conceptual sense. Libertarians can still use this idea in order to explain themselves.

2) Can libertarianism be north-wing when ‘real liberty’ is either to be found in another wing or it is an ‘essentially contested concept’ (Gallie, 1955)?

If pressed, a libertarian could, in this context at least, concede the libertarian/authoritarian contrast. The choice/control (or state-free/state-controlled) contrast can be accepted as more neutral. He can still preserve the essential north/south distinction that enables his own political position to be more easily understood. This also has the advantage of objectively solving Lilie’s philosophical problem of categorising or avoiding issues where the “true libertarian” policy is debatable (Boaz 1986, p. 88).

However, to object to the name ‘libertarian’ altogether would seem unfair. It is polite debating practice to allow each ideology to be named by its advocates. There are some generally positive connotations to ‘conservative’ and ‘socialist’ that it would be equally trivial to complain about.

3) A more radical criticism, sometimes put forward by libertarians, is that the personal/property distinction is not coherent.

These are really two aspects of any human activity: the body is in a broad sense property (or an economic resource); external goods are at some point tied up with someone’s personal projects. So, the libertarian might insist, only the north/south (original left/right) axis makes proper sense, and we cannot have the other axis (and so cannot have the Compass).[9]

I see considerable force in this point and so reject the view expressed by Maddox and Lilie that “the extent and nature of government regulation of personal behaviour ... is both analytically and empirically distinct from conflict on the economic dimension” (Maddox and Lilie 1984, p. 4, emphasis added). Nevertheless, moral and political distinctions are conventionally made between what are called ‘personal’ and ‘property’ issues. I cannot see why these distinctions ought to be entirely ignored because they are indeterminate from a purely conceptual viewpoint. This would be as unfortunate an excuse for continued confusion and dogmatism as is the current insistence on only the modem left/right division. As Brittan puts it,

Relationships between views on different subjects do not have the authority of logic or mathematics. There are historical, sociological and cultural explanations why a bias towards economic freedom should be combined with an anti-permissive approach to social questions and relatively belligerent external attitudes among Conservatives—just as there are for the combination of state economic intervention, a bias towards freedom in personal behaviour and pacific external attitudes among the Labour Party (1968, p. 142).[10]

The distinction between personal and property choice is conceptually dubious but it is a socio-political reality (somewhat like the mediaeval distinction between ordinary women and witches). And this reality can be illustrated graphically without conceding that it is conceptually coherent. Perhaps by this display people will eventually be brought round to abandoning the current left-right view. But it is a mistake to insist on a choice/control axis without allowing people a clear view of how it relates to the modem left/right view. This is to require an intellectual effort that will be too much for most people, due to lack of real interest in politics, as well as an unnecessarily immediate rejection of their comfortable orthodox distinction.

4) It might also be suggested that we could, in principle, introduce all sorts of theoretical dimensions to complicate the simple left/right one.

I believe that the preceding account captures something very significant politically[11] while not moving too far beyond the popular, simpler distinction to be impractical for general use. Maddox and Lilie show that even ‘foreign policy’ is also clearly divisible into these four winged approaches (Maddox and Lilie 1984, ch. VII). Samuel Brittan made various attempts to improve on the left/right view (Brittan 1968, pp. 88-89), but none of them appears to have the simplicity and verisimilitude of the view defended here. In the quoted passages, Brittan clearly sees that the personal/property distinction exists, but he does not home in on it as the solution to the mess (perhaps because he is, ideologically, too near the centre of mainstream politics).

In reality, then, it is non-libertarians who are being tendentious if they insist that libertarianism is on the ‘extreme right-wing’. This usage is merely a pejorative and an excuse to avoid debate. But now libertarians can, if necessary, practice tit-for-tat by lumping together non-libertarians as undifferentiated ‘south-wingers’ or ‘authoritarians’.

As more people become libertarians, especially more academics and other intellectuals, we might find that their insistence on being ‘north-wingers’, if they do so insist, gives currency to this interpretation of the Political Compass. The modern political terms ‘left’ and ‘right’ will not disappear in a hurry, if at all, but they do not need to. Though if the Political Compass were to become popular then ‘left’ might sometimes become ‘west’ and ‘right’ become ‘east’.

A Political Compass Quiz

Marshall Fritz offers a quiz with only five very general questions for each axis (Bergland 1990, pp. 22-23). The following quiz has ten questions each. These questions are still relatively few and selective. They might fail to place some readers in the proper area.[12] They are roughly in ascending order of extremity, from a conventional viewpoint, of anti-statism. They have been thought up both to clarify the general idea of the Political Compass and to elucidate the nature of the libertarian (choice or state-free) north-wing.

Some questions might seem to be partly relevant to the opposite category. To some extent this is because what are roughly distinguishable as personal and property aspects are contingently bound together in certain issues. But this is also because of the truth of the criticism that the distinction is conceptually dubious.

To give an absolute position on figure 3, and thereby the Compass, give yourself one point on the appropriate axis for each ‘Yes’ answer (or a fraction of a point to the extent that you agree).

Personal Choice Questions

1) Should people be allowed to follow their own religions in peace and privacy?

2) Should women be allowed contraception and abortions?

3) Should all consenting, private, adult sexual acts be legal?

4) Should all state censorship be abolished?

5) Should employers be allowed to discriminate on any basis they like?

6) Should all drugs be legal?

7) Should all voluntary human sports, no matter how violent, be legal?

8) Should crimes be seen as only against individuals, or private institutions, who are due restitution from the criminals?

9) Should the few political figures responsible for a war be targeted rather than civilians and conscripts?

10) Should state immigration controls be replaced by private-property controls on entry?

Property Choice Questions

1) Should the state stop using taxes to subsidise art and entertainment?

2) Should the state stop using taxes to subsidise industries?

3) Should all state barriers to free trade be abolished?

4) Should people acquire their education from the market or charity instead of by taxation and state intervention?

5) Should voluntary insurance and charity replace state welfare?

6) Should the state’s coercive monopoly of money be abolished?

7) Should all roads and streets be privately owned and regulated?

8) Should private ownership be allowed to deal with environmental problems?

9) Should all taxation stop because it is extortion?

10) Should the state’s coercive monopoly of law and its enforcement be replaced by competing protection agencies?

Notes

[1] However, nothing about the suggested Political Compass depends on this interpretation being true.

[2] An interesting attempt to make sense of this from a libertarian viewpoint is Jerome Tucille (1970, p. 38). There libertarianism is placed as more extreme than fascism and communism. I cannot see how this really clarifies matters, despite the accompanying explanation.

[3] In Britain, the Revolutionary Communist Party (or at least one RCP debater at the LSE) put Hitler and Stalin on the far right, but themselves, Lenin, and classical liberals on the left. If they mean that we are all anti-authoritarian in principle then that is a return to the old labels (in principle—but we have a considerable factual dispute about what is anti-authoritarian in practice).

[4] As Z. Sternhell puts it in The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought’s entry on ‘fascism’, “Totalitarianism is the very essence of fascism, and fascism is without question the purest example of totalitarian ideology” (Miller 1987, p. 150). He quotes Mussolini’s definition of fascism: “Everything in the state, nothing against the state, nothing outside the state.”

[5] “Political map” is the expression Marshal Fritz uses.

[6] Liberal (for personal freedom [+PF] and for government intervention in economic affairs [+GE]); libertarian (+PF, -GE); populist (-PF, +GE); conservative (-PF, -GE).

[7] Butler and Stokes (1969), Political Change in Britain, Macmillan, London.

[8] Who, in turn, modified the original idea of Eysenck’s psychological tough-minded/tender-minded distinction (1963).

[9] This was the major criticism of David McDonagh in correspondence. It is apparently implied in Hayek’s view that “To be controlled in our economic pursuits means to be ... controlled in everything” (Hayek 1976, p. 68).

[10] Brittan continues: “But these combinations are not part of the permanent order of things. At least as good a case can be made for putting together in Cobdenite fashion economic and personal freedom and non-intervention overseas.”

[11] As Brittan shows is true in the UK, in both cited books, and the work of Maddox and Lilie bears this out for the USA.

[12] My interest being primarily philosophical, I set aside detailed empirical refinements. It is probably clearer to plot ideologies and not political personalities (as do Brittan and, to a lesser extent, Maddox and Lilie).

References

Bergland, D. (1990), Libertarianism in One Lesson, Orpheus Publications, Costa Mesa, CA.

Boaz, D. ed. (1986), Left, Right and Babyboom: America’s New Politics, Cato Institute, Washington.

Brittan, S. (1968), Left or Right: the Bogus Dilemma, Secker and Warburg, London.

Brittan, S. (1973), Capitalism and the Permissive Society, Macmillan, London.

Butler and Stokes (1969), Political Change in Britain, Macmillan, London.

Eysenck, H. (1963), The Psychology of Politics, Routledge, London.

Gallie, W. (1956), “Essentially Contested Concepts” in Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 56, pp. 167-198.

Hayek, F. (1976 [1944]), The Road to Serfdom, Routledge, London and Henley.

Jacobs, E. and Worcester, R. (1990), We British: Britain Under the MORlscope, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London.

Kedourie, E. (1985), The Crossman Confessions and Other Essays in Politics, History and Religion, Mansell Publishing, London.

Maddox, W. and Lilie, S. (1984), Beyond Liberal and Conservative: Reassessing the Political Spectrum, Cato Institute, Washington.

Miller, D. ed. (1987), The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, Basil Blackwell Oxford

Rothbard, M. (1979), Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty, Cato Institute, Washington.

Tucille, J. (1970), Radical Libertarianism, Bobbs-Merrill, New York